Saturday, December 4, 2010

reflective journal

It has been so interesting to take this course at the same time as I began work as a school librarian. Already I can see both ways that topics raised in our course apply to the real world of librarianship, as well as obstacles that come up when theory starts to get put into practice.

A theme that I've considered often over the course of this semester is the dynamic nature of librarianship. This seems like a profession that is continuously changing and evolving, or at least has the potential to. I know from my years as a classroom teacher that routines are necessary in schools, but that it's easy for a routine to become a rut. I'm wondering about how I will stay on top of developments and new ideas in the field, once I'm out of library school. I also wonder about collaboration. It's been great to have classes full of colleagues and professors who are all interested in school librarianship, who are available for brainstorming with and bouncing questions around. How will the nature of collegiality change if I'm the only librarian at a school? What are some other avenues for collaboration and professional affinity?

My worries:

-finding a (full-time) job at all

-budget woes

-getting to know a collection well enough to be able to match books with all sorts of readers (how do librarians do this? it seems like magic to me)

-getting to know hundreds of students instead of one class at a time, and wondering if relationships with so many kids at once will be as fulfilling as those were with my first grade students

Budget and job searching issues notwithstanding, I think that my other worries will be resolved just by having more time and experience actually working as a librarian, and bridging that theory-practice divide. I appreciate that many of our assignments have focused on practical tools that could be used in a real life library setting (particularly the tech tools).

Overall, I feel hopeful about the potential for school libraries and excited (if sometimes intimidated) about getting further into the profession. I think it's important work. I hope I'm up to the task.

Saturday, November 13, 2010

school libraries and advocacy

What is the role of advocacy in the school library? To whom should you apply advocacy efforts, why? In investigating advocacy efforts what do you see that you like? What concerns do you have? What challenges are facing school libraries?

There always seems to come a point in classes where I hit the theory-vs.-practice wall. That is to say, I read or hear or learn things in my courses that sound good in theory, but I’m not quite sure how I will implement them in my practice as a school librarian. Advocacy is somewhat like that for me. I think advocating for the importance of school libraries (and library funding, programming, resources, etc.) is tremendously important, and an undeniable necessity in this profession right now. But it’s hard to know what it looks like in practice—or how to find the time to do it.

Given all of that, I really appreciate the depth of the resources at the AASL website— to know that there are ready-made, readily available sources of information and advocacy ideas is so helpful. All of the advocacy toolkits are resources I can definitely imagine using and revisiting over and over again. They really help distill a big concept like advocacy into manageable, easy to understand ideas and suggestions for action.

While I’m not totally sure how advocacy efforts fit into the day to day workings of a school library, I do feel like those efforts should be an integrated piece of any school library program, as opposed to an afterthought added in only occasionally. I work in a school library right now which is exceptional in several ways—it is well-funded, with three library staff members (for a 500 student school); there is money for new books and author visits and professional development, and a good deal of collaboration with classroom teachers. At first glance, an outside observer might argue that there’s relatively little need for library advocacy. But I see the ways it is a part of the head librarian’s thinking all the time. Whether it’s creating a parent volunteer program, holding community events in the library, or thinking of ways to partner with other local schools with fewer library resrouces, there is a consistent, subtle way that she is promoting the library all the time. The goal is for the library to feel like (and be) an essential part of the school community, and for the community members to feel connected to the library. This work is ongoing.

Certainly contemporary libraries are challenged by budget constraints, first and foremost, and advocacy is necessary on all levels. From library promotion efforts in individual schools, to events like the ALA’s annual Library Advocacy Day, getting the message out that libraries are essential to learning is critical. We need to be able to explain why our efforts and programs are important to all kinds of stakeholders—students, parents, administrators, school boards, etc. Fortunately, there seem to be lots of resources out there to help librarians navigate the terrain of advocacy, and put theory into practice.

Saturday, October 30, 2010

shhh... don't tell the ala

I love the ALA. I love that they’re fighting the good fight on important issues, and I am proud to be a card-carrying member of what I think is an important organization. I think that, theoretically, the ALA’s position statements on intellectual freedom are reasonable and aspirational and certainly well thought out. But to me, these statements deal too much in the realm of theory and don’t provide a lot of guidance to librarians in practice (which is fine-- this is just to say that they feel incomplete to me). It also seems, though I don’t know, that the ALA’s position statements apply more easily to public libraries, and that school libraries might face issues of intellectual freedom and censorship in different ways.

The ALA’s statement on Access for Children and Young Adults to Nonprint Materials states: “Recognizing that librarians cannot act in loco parentis, ALA acknowledges and supports the exercise by parents of their responsibility to guide their own children's reading and viewing” (www.ala.org, 2010). I understand that public librarians don’t (and needn’t) act in loco parentis, but I think that statement gets a lot blurrier in a school setting. Teachers do act in loco parentis in all sorts of ways.

Here is my question about nonprint materials: would the ALA condone unrestricted internet access in school libraries? I agree with the ALA’s statement that students should have unfettered access to “a diversity of content and format.” Surely, though, there is information that is so obscene or age-inappropriate that exposing children to it could be harmful to them. School libraries have collection development policies-- books that are appropriate for students are chosen by librarians. Not every book that is published is one that students have access to in school. I believe it should be the same for nonprint resources like the internet. I don’t think children should have unsupervised, unfettered access to the internet. I don’t know much about how filtering software works, but I feel that some level of guidance toward appropriate resources is necessary in school libraries.

As for labeling and rating systems, this is another area where the gap between theory and practice leaves something to be desired. I understand the ALA’s position that adding ratings or other labels to materials that aren’t part of the published product (ratings on movies or video games, for example) is a form of censorship, as it can either implicitly or explicitly limit a student’s access to library materials. However. I believe there are times where some guidance is appropriate and necessary. I think it’s important to consider the intent of the ratings, and the impact that they have. Are ratings there to provide guidance or to deliberately restrict access? It reminds me of the early 1990’s debate over warning labels on music, and the sale of certain music requiring parental consent. Here’s how I feel: warning label= okay; requiring parental consent= not okay. That’s essentially how I feel here.

The other question that comes up for me is, who is doing the labeling? When big bad Accelerated Reader adds ratings for its books, that makes me suspicious (though again, I don’t have a huge problem with it unless books rated MG+ aren’t made available to students who want to read them). If librarians create systems that work for their libraries and their communities, I have less of a problem with that. I realize that puts a lot of power in the hands of librarians, but I think we’re a pretty trustworthy bunch.

An example from the real world. I work in a K-8 private school library. The head librarian is a big proponent of YA literature, and has worked hard to create a teen section that will appeal to middle school readers. Books in the teen section that have particularly mature content or language have a red dot on the barcode-- 7th and 8th graders may check these books out freely, though K-6th grade students need parental permission to do so. I think the ALA would be super cranky about this. To me, it makes practical sense. A book for an 8th grader might really not be appropriate for a 2nd grader. Are the 2nd graders prohibited from browsing through the teen books? No. If a second grader wanted to borrow Twilight (or Breaking Dawn, for that matter), do I think a parent might want to weigh in? Yes. Could I find that second grader a really exciting book about love and vampires that was more age appropriate in the meantime? Sure. If the parent gave their consent, would I have a problem with a 2nd grader checking the book out? Nope.

Could guidelines such as the red dot system be misused and infringe on students’ intellectual freedom? Absolutely, but not necessarily. The head librarian at my school explained to me that this system has freed her up to develop a really rich and varied teen collection, without fretting too much about potentially mature themes or language. So it’s complicated.

No matter what a school library’s policies are regarding intellectual freedom and access to information, they should be clearly communicated to families, through collection development policies, letters home, or other means of family education. And we should of course continually be teaching students how to evaluate books and nonprint materials for themselves.

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

reflective journal: what's in a name?

What is in a name? Over the last 25 years (probably longer) the title of school librarian has morphed from school librarian to media specialist to teacher librarian. In Canada and California, and maybe other places we are officially teacher librarians. According to AASL we are school librarians. You would be amazed (or at least I am) at the debate and passion this issue incurs. A recent webinar explored the issue, right after AASL's announcement - yes, we are school librarians. What is your take? Does the name matter? Why? Which would you choose? Why?

What is in a name? Over the last 25 years (probably longer) the title of school librarian has morphed from school librarian to media specialist to teacher librarian. In Canada and California, and maybe other places we are officially teacher librarians. According to AASL we are school librarians. You would be amazed (or at least I am) at the debate and passion this issue incurs. A recent webinar explored the issue, right after AASL's announcement - yes, we are school librarians. What is your take? Does the name matter? Why? Which would you choose? Why? I have a lot of thoughts about this seemingly innocuous question. Or two questions, really: What do we call ourselves? And, does it matter? I had to go with bullet points here, because my thoughts on this are flying in many different directions.

- It strikes me that this conversation, both the tone of the AASL discussion and the topic itself, reflects a profession that is somewhat in crisis, or at least in flux. If everything is hunky dory and things are going well, then you need to don’t devote a year of time to decide what to call yourself. The thrust of the AASL conversation was about branding and identity to the larger community, but I also feel that part of this question stems from the evolving self-identity of librarians, as well as the pressure of needing to continuously justify the importance of our work. So my first question is, who are we trying to define ourselves for? The public? Ourselves? Both?

- There was a lot of talk in the AASL webinar about the shift from an emphasis on information to an emphasis on knowledge. I like this. It reflects the shift in the research from a focus on “information literacy” to “guided inquiry." I think we’ve talked about this in class, too—the idea that information is the means, not the end. In some ways, I think this shift is about an acclimation to an information-saturated world. Perhaps 20 years ago the conversation was about, “Hey wow, look at all of this information!” And now it’s a given that the information is there, and the focus is on what we do with it.

- The move toward (or back to) school librarian as the “official” title for our profession is a way of re-encompassing what librarians do and are responsible for. I don’t know the whole history, but I can imagine that job titles like Library Media Teacher/Specialist and Information Technology High Priestess emerged due to changes in the profession and in school libraries. If librarians weren’t only reading books and helping with print reference anymore, but were doing more media and technology-related work, then perhaps some felt that a new title was needed to reflect these changes. Now I feel like there’s a move to bring it back and say, yes, libraries are changing and librarians are in charge of all of this— books and tech and computers and kindles and reference and databases and all of it— to sort of bring it all back in under the umbrella of librarianship. I appreciate that—it strikes me as a more integrative step than fracturing the job title. It’s post-postmodern!

- That said, I kind of think people should get to call themselves what they want, as a general rule, though I suppose professional associations get to be a little bit fascist about it, if they want to be. It was interesting for me to read some of the comments on the ALA and AASL websites about this issue—some school librarians clearly felt strongly about their professional identity and job title. So yes, names do matter. And I think there’s room for variation, too. I think what’s ultimately most important is that our role is clear to our students, teachers and families that we serve. “School librarian” is simple, direct, and to the point. I must say, I also like teacher-librarian. But maybe the “teacher” should be implied? Like all librarians are teachers?

- I identify myself a school librarian, so I am happy to accept this AASL guideline. I think it’s an appropriate name. It’s easily understood, and it’s broad enough to encompass the many facets of contemporary librarianship.

Saturday, October 2, 2010

mission statements

I feel as though some of the nine common beliefs could almost be mission statements by themselves. In terms of considering them through the lens of the mission statement, I think the most relevant and important beliefs are “School libraries are essential to the development of learning skills” and “The definition of information literacy has become more complex as resources and technologies have changed.” Both of these statements frame school libraries as central to learning, critical thinking, and skill building for 21st century learners. Some of the other beliefs are important, but perhaps not at the core of what school libraries are about. For example, I agree that “Ethical behavior in the use of information must be taught.” But this isn’t quite big enough an idea for a mission statement, in my opinion.

If I was going to write a school library mission statement, I think the most important ideas to include would be:

- The goal of literacy in multiple forms (information literacy, media literacy) along with comfort and engagement with the printed word

- The goal of helping students critically evaluate information (from encyclopedias to databases to tweets), to better prepare them to engage with the world around them

- Promoting inquiry, curiosity, and self-directed exploration

- Integration of technology into teaching and learning in the library

- The library as a site where community members (students, teachers, parents, administrators, etc.) can come together to interact, collaborate, and learn.

Even as I’m looking at this list, I feel like maybe that’s too much for a mission statement. There’s a lot that I believe libraries can be, so it’s hard to whittle it down to just a few meaningful sentences.

I’m reminded of Joshua Prince-Ramus’s fabulous TED talk about designing the Seattle Public Library building. He presented a diagram that showed the evolution of the public library—how public libraries began with a narrower focus that has expanded over time.

Though he’s talking about public libraries, I feel like this evolution is echoed in the role of school libraries, due if nothing else to the expansion of information in our culture. That libraries can be many things to many people is part of their magic, and yet it’s important to have a clearly defined mission and message.

So I’m not sure if my reactions to the Common Beliefs have changed- I still think they’re pretty fabulous and definitely relevant. Some strike me as more “mission statement worthy” than others, but they are a reminder that defining our goals and beliefs is an important step in achieving them.

Saturday, September 18, 2010

reflective journal: the aasl's 9 common beliefs

Read the 9 Common Beliefs (AASL_Learning_Standards_2007.pdf). Do you agree with them? What concerns you? excites you? is interesting? What questions do you have? How do they relate to current educational paradigms, philosophies, and/or policies?

God bless the AASL. Here’s to the researchers, educators, and librarians who thoughtfully codified these nine beliefs and learning standards. (Incidentally, I’m curious to compare the AASL library standards with those adopted by the California Department of Education this week, to see where they overlap and where they don’t.)

So, yes. The short version is: I’m on board with these common beliefs.

Here’s the longer version:

The AASL’s Common Beliefs strike me as a very pragmatic, thoughtful, forward-thinking collection of tenets that would serve as a useful guide for school library professionals, particularly pre-service librarians. I started my first school library job last week and I am thrilled to have a guide like this as I begin my first foray into this profession.

I like that these beliefs address specific and important components of the LIS realm, but are broad enough to be applied in a variety of contexts. I’m amazed and baffled that while educators across disciplines echo the sentiments of these beliefs and consider them among best practices, our educational system is so focused on discrete skills, standards, and testing, testing, testing. Who’s got time for inquiry? Sheesh.

I was struck by the inclusion of “texts in all formats” in the first belief, Reading is a window to the world. Raising pictures and video to the level of print is appropriate, I think, but potentially controversial. I appreciated also the assertion that reading includes decoding and comprehension of texts, but extends into critical thinking skills too. I like the focus on creating independent learners. It seems to me that a main theme of this document is that today’s students must learn how to reliably and critically evaluate information for themselves. Cultivating an attitude of inquiry and curiosity aids in the development of information literacy, especially when coupled with the technical and technological skills to support that curiosity. The emphasis on equity is an important one, as is the call for teaching ethical behavior. That learning has a social context isn’t a new idea in the world of education, but it was interesting to see this belief reconceptualized and applied to the digital world.

I especially appreciated the last belief: School libraries are essential to the development of learning skills. To me, the breadth of the Common Beliefs is a positive and a potential negative at the same time. That these core ideas could be applied to all aspects of school curricula is a testament to their relevance and usefulness. Inquiry-based learning in a social context is a concept that educators across disciplines can get behind, as are equitable access, ethical behavior, and the development of information literacy and technology skills. It is crucial, though that we as LIS professionals continuously make the case that these types of learning and skill building happen potently in libraries, and we must make sure that they do. In other words, reading books in the classroom isn’t enough, nor is working toward equity in only non-library areas of the curriculum. It seems to me (if my wiki research is any indication), that school librarians must continuously justify their role. The AASL’s Common Beliefs seems like a good way to start.

Saturday, September 4, 2010

reflective journal: library memories

Describe your current understanding of the role and mission of school libraries. What are/have been your experiences with school libraries and how has this colored your understandings of what a school library is and should be?

I remember my elementary school library. It was at a major hallway intersection of the school; we would all walk past it on the way from our classrooms to the multi-purpose room for lunch or gym. Mobiles hung from the ceiling. My fellow classmates and I would sit on the floor, Indian-style, if you please (it was the 70s—we still called it Indian-style), and listen to the books the librarian read. Probably we checked books out as well, but I can’t remember.

In middle school, the library was a secret getaway, a place to practice skulking in corners and to read the current issues of YM and Seventeen, which my friends and I couldn’t believe were allowed in the library, since they weren’t “educational.” Looking up racy words in the dictionary was another fine sport (I was kind of a nerd in middle school).

My high school library was primarily a place to study. Occasionally a teacher would bring us for the librarian’s presentation on research methods. This involved a lot of 3x5 index cards, but nothing else too memorable. It was pre-internet, so there was no irresistible cosmic pull to the computers. By this point, my allegiance was with the public library, where I could take out books about psychology and travel and underwater life and craft projects by the armful.

I realized, during my little trip down school library memory lane, that I have always related to libraries as someone who likes to read. As I have moved into the role of teacher and now school librarian, I encounter kids who love reading, but many reluctant readers as well. When I compare my memories of school libraries as a student with my observations as an adult and teacher, I realize that school libraries present the opportunity for students to relate to the library in their own individual ways. For some students, the library is haven. Others may feel neutral or actively disinterested in the goings-on of the library. I think it’s our job as school librarians to create and promote multiple access points for students (and teachers, and parents) to connect with books and information in ways that are authentic, personalized, and meaningful.

School libraries are unique and vital because, while they can (and should) be an integral component of school life, they exist in a slightly removed realm from the classroom. I feel like students can enter the library on their own turf—with their own interests, seeking information that is personally significant—in a more self-directed way than is sometimes afforded by the classroom. Students who find themselves passively receiving information in class can have the opportunity to actively seek out information in the library. With curriculum becoming ever more standardized, and with teaching becoming increasingly about testing in the interest of leaving no child behind, school libraries can become a territory for exploration, creativity, and the pursuit of individual interests.

To me, libraries are about literacy. Information literacy, media literacy, and good old fashioned book reading literacy. With all of the talk about the internet and Web 2.0 tools and Facebook and schools banishing books from their library, it’s still critical to remember that kids still need to learn to read. They need to be inspired and excited by all forms of the printed (spoken, drawn, sung) word. They need to learn to think critically to evaluate information and make connections. Occasionally they need to skulk in corners and read Seventeen, and make their own memories about what a school library is.

Monday, August 9, 2010

yay, ya!

The biggest reason adults are reading YA and tween books is the simplest, says Paul: they're just great books. They are exciting, suspenseful, and fun. You don't have to work too hard at them. They're straightforward, heartfelt, and satisfying. There are books written in a series, and there is tremendous collective excitement and suspense as fans anticipate new additions featuring their favorite characters and settings (the hype Paul describes surrounding the forthcoming release of Stephanie Collins' Mocking Jay almost makes me want to try reading The Hunger Games again, but for the pesky dead children theme).

As the field of tween and YA literature has grown and expanded, this genre has made a name for itself as innovative, fresh, and exciting. Why wouldn't adults want to read along? This article made me think about my own experiences with the genre-- leaving a wedding early to stand in line for the midnight release of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, laughing along with Diary of a Wimpy Kid (and incessantly saying "Bink says Boo!"), introducing the Eragon audio book to my husband, who now enjoys his hour long commute to work, but mostly thinking about kids out there enjoying the same books. Not only do adults want to read these books, but kids want to read them. And that is the whole point.

Paul, Pamela. "The Kids' Books Are All Right." The New York Times - Breaking News, World News & Multimedia. 6 Aug. 2010. Web. Retrieved 10 Aug. 2010 from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/08/books/review/Paul-t.html?_r=3&ref=books

Sunday, August 8, 2010

a series of unfortunate events

Snicket, L. (1999). The bad beginning. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Snicket, L. (1999). The bad beginning. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.ISBN: 978-0064407663

Lemony Snicket. Don't you want to read books written by a person called Lemony Snicket? Even if it is a pseudonym?

The Bad Beginning (and the subsequent 12 books in this series) chronicles the misadventures of Violet, Klaus, and Sunny Baudelaire, three siblings whose parents have died in a mysterious, tragic fire. With no responsible adults to care for them, the Baudelaires are left to their own devices to survive--and prevail over the evil Count Olaf, a most delicious villain who is intent on claiming the Baudelaire fortune.

The books follow a fairly predictable plot structure—near-misses, dangerous scrapes, inept adults, crazy inventions, bravery, and constant exhortations to stop reading (a delightful bit of reverse psychology that works). Snicket's lyrical, verbose writing is as much a character as any of the people in the series; puns and impressive vocabulary words are peppered throughout. Each book ends with a bit of a cliffhanger, and readers will want to read through the whole series to see what becomes of the Baudelaires. The ending isn't happy. But you are warned at the beginning that it won't be. A fabulous read aloud selection; great also for a third or fourth grader looking to get hooked on a series.

Saturday, August 7, 2010

charlie and the chocolate factory

Like Oliver Twist before him, and Harry Potter since, the odds are stacked against Charlie Bucket. Poor, worried, and well aware of the injustices in the world, he goes through life quiet, lonely, and a bit sad. Unlike Oliver and Harry, however, Charlie has the support of a loving family, including four grandparents who never leave their bed (and provide comic relief). Charlie’s hometown is dominated by the presence of Willy Wonka’s mysterious chocolate factory, a place where “Nobody ever goes in—and nobody ever comes out.”

alice's adventures in wonderland

ISBN: 978-0230015135

Forget Disney, or even Tim Burton: this is the wild, trippy original. With lush language and adventure at every turn, this rambling ride would be a fun choice for tweens who are good readers with a bit of patience. The writing style may elude some; for those ready for it, it's a treat.

freaky friday

Friday, August 6, 2010

censorship and the role of the librarian

Apparantly, a librarian did just that recently, and it's causing an uproar. According to School Library Journal, the library director of the Burlington Country Library System in Burlington, NJ has issued a directive that all copies of Revolutionary Voices: A Multicultural Queer Youth Anthology (Alyson, 2000) be removed from circulation. The librarian did this despite no formal challenge being raised, and cited child pornography as the reason for the removal of the book. The book in question has earned praise from School Library Journal as well as GLSEN (The Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network). It is unclear exactly what prompted the librarian to order the book's removal, but her decision was upheld by the Library System's Board of Commissioners.

It's hard to tell from the outside, but this seems like a pretty outrageous and egregious exercise of power. It also reminds me of the enormous power librarians possess as gatekeepers of information, and the restraint with which that power needs to be exercised. Certainly, if a book is genuinely pornographic, that I say, get it out of the library.* But it's hard to believe that whoever works in collections development is choosing pornographic titles for the library. Also disturbing is the lack of a clear challenge to this book. There might be occasions where it is truly appropriate to remove a book that is inappropriate or offensive, based on concerns raised by the community.* But in the absence of a clearly documented challenge process, the whole situation winds up feeling fishy to me, especially given the "controversial" nature of this book. The irony, of course, is that there may be tweens out there who desperately need exactly this book, and it's a shame for their information access to be muddled in this way.

*cue the ALA and their pitchforks...

Barack, L. (2010, July 27). NJ library, citing child pornography, removes GLBT book. School Library Journal, Retrieved from http://www.schoollibraryjournal.com/slj/home/886066-312/nj_library_citing_child_pornography.html.csp

UPDATE: Not such a random act by this librarian after all. The

teens cook

ISBN: 978-1580085847

With recipes like Baked French Toast, Taco Salad, and Eggplant Parmesan, Teens Cook is an appealing primer for those interested in getting into the kitchen. Recipes for breakfasts, snacks, family meals, and desserts are included, and instructions are straightforward. This book was written by two teenagers, which lends it an air of credibility.

meanwhile

ISBN: 978-0810984233

A maze, comic book, and choose your own adventure in one, Meanwhile is a fun, innovative book that former Captain Underpants fans are sure to enjoy. Jason Shiga's innovative graphic style and inventive book format, full of puzzles and codes, are pleasing to the eye and to the mind. Full of robots, invetions, and time travel, it's great fun, perhaps especially for reluctant readers.

ella enchanted

ISBN: 978-0060275112

A retold fairy tale reminiscent of Cinderella, Ella Enchanted tells the story of Ella, a girl cursed with an unusual personality trait: she is compelled to obey whatever she is told to do. This becomes a liability, and Ella begins a quest to rid herself of this spell. Full of princes, fairies, and other fantastic creatures, this Newbery honor book is a delightful read.

because of winn-dixie

ISBN: 978-0763644321

"My name is India Opal Buloni, and last summer my daddy, the preacher, sent me to the store for a box of macaroni-and-cheese, some white rice, and two tomatoes and I came back with a dog."

So begins Because of Winn-Dixie, named for the dog that India finds, who she names after the grocery store where she finds him. He's big, dirty, and strange looking, but he's friendly, and he can smile. Winn-Dixie is Opal's constant companion as she comes to know her new neighbors in Naomi, Florida, the town where she and her father have just moved to. She meets Amanda Wilkinson, a girl with a pinched, sad face; Miss Franny Block, the town librarian, and Gloria Dump, and old, blind woman who the neighborhood children fear, and Otis, the clerk at the local pet store, who plays his guitar for the animals. Each person Opal meets has their own secret sadness, and it is the revelation of the shared experience of sadness that ultimately connects them all.

A Newberry honor recipient, this small, spare book is perfect for tucking in your pocket on a summer day. The subtle themes may be more appreciated be slightly older tweens.

eragon

ISBN: 978-0440240730

For those finished with Harry Potter but not quite ready for The Lord of the Rings, who are looking for another meaty series full of fantasy and adventure, then Eragon and the Inheritance trilogy might be just the thing. When Eragon finds a mysterious blue egg, it opens up a whole new world of adventure. An exciting tale of good and evil.

bad news for outlaws

ISBN: 978-0822567646

This Coretta Scott King award winner profiles Bass Reeves, an African-American deputy U.S. marshal in the Wild West in the late 1800s. Included is a glossary of terms, a timeline of Reeves' life, and a bibliography with suggestions for further reading. A fascinating true story.

Thursday, August 5, 2010

rapunzel's revenge

ISBN: 978-1599900704

A fun retelling of a classic tale; this Rapunzel story isn't for little kids. After using her long hair to escape from her castle tower, Rapunzel discovers a new world outside of the castle walls, wholly different from what she's experienced before. She teams up with Jack (of Beanstalk fame), to defeat an evil witch who is terrorizing the kingdom. Witty dialogue and smart illustrations make this a great read.

the strange case of origami yoda

ISBN: 978-0810984257

Hooray for books that are pure fun. The action here centers around a sixth grade class, Dwight, a "weird" outcast, and his paper Yoda finger puppet that is unusually wise. Is Origami Yoda real or not? A fun summer book that even reluctant readers will enjoy.

Wednesday, August 4, 2010

american girl magazine

One of my favorite Hebrew words is stam. It's a word that's a little hard to define, but essentially means "ordinary" or "for no particular reason." You can use stam to describe things that just are the way they are, things that are inexplicably unremarkable, or maybe a little boring.

To me, American Girl Magazine is sort of stam. Not terrible, just not particularly innovative. It covers general topics of interest to young tweens: friends, craft projects, quizzes, stories, and helps keep the AG empire intact. Sort of girl power lite.

the egypt game

ISBN: 978-1435211827

A group of friends get involved in creating an elaborate game based on their fascination with ancient Egypt. This book, a 1968 Newbery Honor recipient, is full of mystery, intrigue, and adventure. A middle school English class mainstay, this one's good enough to read just for fun.

where the wild things are

This lovely, haunting movie is an adaptation of Maurice Sendak's classic, Caldecott Award-winning picture book. Tweens may think this is a little kids' movie at first, but its themes are quite mature and deep. A less sensitive treatment of the material wouldn't have benefited this well-loved book, but this beautiful film gives new dimension to the original story.

harry potter

J.K. Rowling

Okay, so I'm not breaking any new ground here, but no collection of tween titles would be complete without mentioning good old Harry, Hogwarts, and You-Know-Who. Readers who have already encountered this series in book or movie form may enjoy a second go-round, especially since gulping down the books to satisfy curiosity about the plot may have caused readers to miss some of the more subtle and lovely moments (or maybe that was just my experience). The expressive audiobooks are the perfect accompaniment to a family road trip.

Tuesday, August 3, 2010

guys read

dairy queen

ISBN: 978-0618683079

D.J. is a 16 year old daughter, sister, friend, part-time dairy farmer, and football player. Dairy Queen follows D.J. as she struggles to reconcile all of these roles with each other, and within herself. The smart yet conversational tone of the writing makes it a winning read. "Officially" designated as a young adult novel, tweens who enjoy reading up will respond to this coming of age story. Read the book, then watch the episode of Glee where Kurt tries out for the football team; a perfect pairing.

the golden compass

ISBN: 978-0679879244

Reminiscent of the Chronicles of Narnia and The Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Golden Compass is suspenseful, spiritual, and exciting. The story follows Lyra through an epic adventure full of witches, talking animals, and mysterious creatures. The first in the three-volume His Dark Materials trilogy.

coraline

McKean, D., & Gaiman, N. (2002). Coraline. New York: HarperCollins.

ISBN: 978-0380977789

Not for the faint of heart, Coraline is a suspenseful, finely-drawn thriller. When young Coraline discovers a secret world, strangely parallel to her own, she is faced with a choice: where does she want to remain? When things go terribly wrong, it is up to Coraline to save herself and her family. Beautifully written and totally creepy, Coraline has been adapted into a graphic novel and a movie.

summer reading

Me: "What's your summer reading this year?"

My 17 year old brother: "Oh, The Odyssey and some other sh*t."

I had to laugh.The Odyssey was written about 3000 years ago, and has probably been assigned to every high school or college student to read since then. Presumably, my brother's English teacher has some good reason for assigning The Odyssey. Does that make my brother excited to jump into his summer reading? Not so much. Give him the 497 page manual for his Emergency Medical Technician training course, or Facebook, and he's perfectly happy to read. Reading about colleges holds his interest; also reading texts from friends. Should this sort of summer reading "count?"

According to Tara Parker-Pope, yes. In her article, "Summer Must-Read for Kids? Any Book," Parker-Pope describes the academic benefits of children continuing to read over summer vacation. According to a University of Tennessee study, a group of low-income students retained reading skills over the summer when given high-interest books to read during vacation, as compared to students who didn't have access to books. The key to the success of this project, researchers asserted, was letting students choose books that were of interest to them; books like biographies of Britney Spears and The Rock, and books connected to popular movies and TV shows like Hannah Montana. When children are excited about their reading choices, the article claims, they read more. And reading more is good.

The students profiled in the University of Tennessee study were first and second graders, but its findings have implications for tween students as well. Librarians have an important role to play in helping connect students of all ages with books and other high interest reading materials. Since teachers (who assign summer reading) and parents may have a specific type of book in mind for tweens to read. Librarians can interact with kids around books without an agenda, and we can empower them to make choices that are exciting and engaging.

photo credit: The Art of Manliness blog, featuring a post on the 50 best books for boys and young men

Monday, August 2, 2010

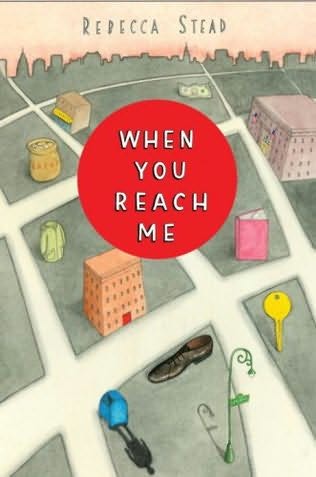

when you reach me

ISBN: 978-0385737425

Winner of the 2010 Newbery Award, When You Reach Me is full of mystery and excitement. The story follows Miranda, the 12 year old protagonist, as she attempts to decipher anonymous notes being sent to her that seem to predict the future. A thrilling puzzle, it is also the story of connections between people, and the transformative power of love and friendship. For a deeper appreciation for this book, read Madeline L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time first; it figures heavily into the plot of When you Reach Me.

the phantom tollbooth

ISBN: 978-0394820378

Milo, a young, bored, boy, discovers a mysterious tollbooth in his bedroom and journeys to Dictionopolis, and readers are invited along on the adventure. A whirlwind of language and puns, this book is an ideal read aloud selection, so readers can mull over the puns and puzzles together. Whimsical illustrations complete this classic.

beezus and ramona

No ma'am. I'm old school.)

the sisterhood of the traveling pants

ISBN: 978-038573058

As the four friends set off for their respective summer adventures, they promise to share the pants equally among themselves throughout the summer. Through letters that accompany the pants, we read each girl’s account of her experiences with them. First thought to be lucky, the pants seem to make already complicated situations worse.

Touching on some YA themes (sex, etc.), this is a good selection for older tweens. This book is a funny, exciting, surprising, and ultimately quite touching testament to the power of friendship.This is the first in a series of four books about the girls and the pants; the first three books were also adapted into a movie.

Sunday, August 1, 2010

on twitter

diary of a wimpy kid

Kinney, J. (2007). Diary of a wimpy kid: Greg Heffley's journal. New York: Amulet Books.

ISBN: 978-0810993136

"Let me just say for the record that I think middle school is the dumbest idea ever invented. You got kids like me who haven't hit their growth spurt yet mixed in with these gorillas who need to shave twice a day." -Greg Heffley

From the opening pages of this "novel in cartoons," we empathize with its narrator, Greg, who is smart, insightful... and wimpy. Greg's words and pictures make up this journal ("not a diary, he is quick to correct us), and through it, we learn about the many trials and tribulations of middle school.

Greg's got a lot to complain about. He's the middle child, stuck between clueless Manny and tyrant Rodrick. He and his best friend, Rowley, aren't getting along like they used to. Girls don't seem to notice him, and he gets kicked off the Safety Patrol for an incident involving a worm. Through it all, Greg keeps his sense of humor, which he channels into drawing comic strips. The comics serve both as illustrations for the reader and as a central component of the plot. They are hilariously funny.

This book's format is a great bridge between traditional novels and the graphic novel medium-- the combination of words and pictures enlivens the story. Greg is a lovable protagonist-- think Bart Simpson but more insightful. A nice choice for those looking for a boy protagonist in a non-fantasy book. A delightful read for adults, too.

harriet the spy

Fitzhugh, Louise. (2008). Harriet the Spy. Paw Prints.

Fitzhugh, Louise. (2008). Harriet the Spy. Paw Prints. ISBN: 978-1435273252

An oldie but goodie-- originally published in 1964. Harriet Welsch, an 11 year old New Yorker, wants to be a writer. With her kind but distant parents constantly busy, Harriet’s most trusted adult is her nanny, Ole Golly. Golly encourages Harriet in her quest to be a writer. To hone her journalism skills, Harriet spies on everyone and writes down her observations in a secret notebook. Harriet is a little odd; her favorite sandwich is tomato and mayonnaise, and while she has good friends, Sport and Janie, she has enemies at school, too.

Saturday, July 31, 2010

squids will be squids

ISBN: 978-0670881352

Who says tweens are too old for picture books? Read Squids Will be Squids to a room full of 4th graders and prepare to have them rolling in the aisles. From the wildly creative minds of Jon Sczieska and Lane Smith, this book is a collection of quirky fables with memorable morals like, "Don't ever listen to a talking bug," and, "He who smelt it, dealt it." Creative, silly fun.

what tweens read

Friday, July 30, 2010

new moon

No, not that New Moon. This is an ad-free magazine, published bi-monthly for tween girls. Setting itself apart from other girls' magazines, New Moon focuses on empowerment, advocacy, and community, and intentionally does not publish articles about diets, how to be popular, or Justin Bieber. Rather than conveying a morally superior tone, the magazine is glossy and fun to read. Girls are involved in writing and producing the magazine, and managing the New Moon website. With articles about reading, science, and community service, this is a cut above your standard teen magazine fare. I'm curious to know what real tweens think of this magazine; as a feminist and the mother of a girl, I think it's fabulous stuff.

No, not that New Moon. This is an ad-free magazine, published bi-monthly for tween girls. Setting itself apart from other girls' magazines, New Moon focuses on empowerment, advocacy, and community, and intentionally does not publish articles about diets, how to be popular, or Justin Bieber. Rather than conveying a morally superior tone, the magazine is glossy and fun to read. Girls are involved in writing and producing the magazine, and managing the New Moon website. With articles about reading, science, and community service, this is a cut above your standard teen magazine fare. I'm curious to know what real tweens think of this magazine; as a feminist and the mother of a girl, I think it's fabulous stuff.

Thursday, July 29, 2010

hoot

ISBN: 978-0375829161

A mysterious running kid, a pancake dynasty, a strange new town, and alligators in the port-a-potties are just some of the characters and plot twists readers will encounter in Hoot, a Newbery honor book for tweens. Roy Eberhart, a recent transplant to Coconut Cove,

Tuesday, July 27, 2010

too old for this, too young for that

Unger, K., & Mosatche, H. S. (2000). Too old for this, too young for that!: Your survival guide for the middle-school years. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Pub.

Unger, K., & Mosatche, H. S. (2000). Too old for this, too young for that!: Your survival guide for the middle-school years. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Pub.ISBN: 978-1575420677

This puberty primer goes beyond the standard “what’s happening to your body” conversation (though that’s included) and explores the social and emotional life of middle schoolers. With chapters on health, self-esteem, emotions, family, and school, this book covers many of the important bases of tweenhood. Quotes from kids enliven the humors, frank text, and “survival tips” are sprinkled throughout. Suggestions of books and websites for further reading are a valuable resource.